Summer and I were getting sick of the day-to-day, mundane, same ol’ same ol’ noon to midnight shifts. Sure, we enjoyed our job. Of course, we loved working together. But we’d been partners for a year, and we were both feeling the itch to move on to the next big thing. For Summer, that meant enrolling back in school. For me? I hadn’t decided yet. I just knew I needed something else.

The email came out one afternoon: “Volunteer crews needed to work for our sister company for 30 days.” We jumped on it immediately. The deal was, we would clock in at our regular station at 7am, drive two hours north to the other company’s station, run calls for them, and then at 5pm drive back to the valley for our 7pm end of shift. Too sweet of a deal to pass up. Twelve hours of pay for eight hours of work? Done.

On our first day, we checked off our equipment thoroughly. I opened the compartment for the drug box and found an orange and white tackle box inside.

“Huh…” I said. Summer laughed at my confusion. This rickety old box felt like it would fall out from the bottom if I tried to carry it by the handle. This box was primitive compared to the new pelican boxes we were used to. Additionally, the truck we were assigned had over four hundred and fifty thousand miles on the odometer. And I thought our dedicated truck at home was high mileage at two hundred thousand miles.

The first shift at our new posting location was fairly boring. We were directed to run the out-of-town transfers – picking the patient up from the hospital and taking them to their new designated facility: psych hospitals, ICU’s, trauma centers, etc… These were the calls that tied up the crews, so they were short-staffed for 911 calls. I was down for it. Transfers never bothered me. Plus, if the patient wasn’t critical, I’d let them sleep and read my book in the airway seat behind them, casually glancing at the monitor for any abnormal vital signs.

Occasionally we did run 911 calls. The first time we arrived on scene with a fire crew, they smiled and chatted with us. Friendliness was something we weren’t use to, but we were grateful. Our patient, a nine thousand year-old man with COPD was having difficulty breathing. Fire obtained all the patient information and when I was satisfied with the information, and the patient was loaded into the ambulance, Summer and I seamlessly went to work administering a breathing treatment and IV.

The fire crew had stood at the back doors of the ambulance watching us, almost confused? I’d assumed at the time they didn’t expect us, an unfamiliar crew, to be comfortable enough with patient care. They tried to help, but Summer and I had a system down. We knew what each other was going to do before we did it.

As we became familiar faces in the town, the fire crews began to relax around us. They’d always been nice, but now they appreciated our presence. Our patient care had spoken for itself.

Transfers were our main priority. It would do the local EMS system no good if their ambulances were stuck on four to eight hour transports when Summer and I were at their disposal. That being the case, we attempted to jump the calls that no one else wanted to take. The thirty-day mark for our assignment had come and gone, but we weren’t complaining. We enjoyed the twenty degree cooler temperature, the relaxed atmosphere, and actually having a station to sit down.

At 4:30pm, a transfer kicked out from the hospital for a behavioral patient going to a psychiatric facility in the valley. We took the call, knowing that it would put us back in town around 6:30, and we would be close to our home station for crew change.

Sam was going to a facility that both Summer and I had transported to a thousand times. This place newer, cleaner, and more up to date than most of the other psych hospitals. It would be an easy transport. I would give Sam a pillow and blanket, turn up the heat a little, and let him fall asleep for the ride.

The nurse gave me report: suicidal indexations, depression, and anxiety. No current plan to hurt himself. Former IV drug user. Cooperative and voluntary. “Nice guy,” the nurse had said, “he just needs help.”

After obtaining all the paperwork, we went into the room to greet our patient. I lightly knocked on the door and announced myself. Sam laid in the ER bed with blankets piled on his lap and a blank stare on his face.

“Hi Sam, I’m Holly and this is Summer. We’re going to be your ride today.”

Sam offered a sad smile and nodded. I asked him if he needed to use the restroom before we departed, and he declined. Gently, he stood up and sat on our gurney. We fastened him with seat belts, the blood pressure cuff, and pulse ox. I informed him that I would take a blood pressure every thirty minutes or so but not to worry. If he just wanted to sit back and relax, I’d be monitoring him the whole ride. Sam nodded and thanked us.

The drive had been smooth. Sam hadn’t said much since we wheeled him out of the hospital. But once we reached the highway, I heard Sam fiddling with the seat belts. I looked over his shoulder and realized he’d removed every last one of them.

“I’m really sorry, I know these are uncomfortable, but everyone is required to be strapped in.” I informed him. “If you like I can loosen them?” I had moved to the bench seat and began refastening the seat belts.

Sam shook his head and tears started to form in the corners of his eyes.

“What’s going on?” I asked, reaching out and putting a hand on his shoulder. “What can I do to make you more comfortable?”

He sucked in a shaky breath. “I have a lot of anxiety and PTSD from being tied down and beaten up.”

I reassured him that he was safe here. I told him, unfortunately, the seat belts were required. “I can put a blanket between you and the straps so you don’t feel them?” I offered. But this was not a suitable solution for Sam who had let the tears fall down his face. “Sam, what can I do to make this more bearable for you?”

He looked up at me and said, “They usually give me Ativan.”

I wasn’t proud of the thought that first ran through my head: Drug seeker. I knew from the paperwork that Sam had received Ativan at the hospital minutes before our arrival. It had been in tablet form, so it would take a while for the effects to kick in. I asked him to be patient with the medication and let it start to absorb in his system and I moved back to my spot at the airway seat. But as the transport continued I found Sam more restless and agitated.

After transporting thousands of psych patients, I was weary. I had learned that you can never not expect the unexpected. Even when a patient was voluntary and cooperative, that didn’t mean they could flip like a light switch and become aggressive. That was how medics ended up wrestling the patient who was trying to escape out the back doors while we were driving 75mph down the freeway. If giving Sam a small dose of sedative kept him happy and calm, I would find a way to do it.

Up again, I moved to the bench seat. I kept my voice calm and even. “Listen, Sam,” I started slowly, “the doctor didn’t give me any orders to give you medications en route. And sometimes if we medicate you, the facility may not accept you when you get there. Then you have to go through this whole process again. Back to the ER, wait for a bed, then be transferred. But I can call and see if I can get orders to give you something. It’s up to you.”

It’s not that I was against giving Sam the medications. In reality, I gave drugs out like candy. Toe pain? Here’s some morphine. Getting a little lippy? Time to ride the van… The Ati-van. But working for our sister company meant there were a different set of rules and protocols. Not to mention, I didn’t have the same drugs I had in the valley. Sure I was well-trained on the drugs they provided, but I preferred my own drug box with my normal drugs.

Sam stated that he understood the risks of returning to the ER if the facility turned him away. “Please, I can’t do this.”

The other issue I faced: I was still bound by my own medical direction. It would have been easy to call the sending hospital, ask for my orders, and carry them out as directed. But since I was not technically one of their employees, on loan from another division, I had to call my doctor to get my orders. Sam wasn’t leaving me much choice, so I sat back in my airway seat and dialed the number.

“Do you need a nurse or doctor?” The voice on the other end of the line asked.

“Doctor for medication orders, please.”

“Hold for Dr. Phillips.”

As I waited, I updated Sam on my progress. “Just waiting to talk to the doctor.”

“This is Dr. Phillips.” His voice was flat and void of emotion.

I cleared my throat. “Hi, Dr. Phillips. This is Holly.” I explained to him that I was a medic transporting a patient to a behavioral hospital. I described Sam’s concerns: that he’d been tied up and beaten which caused him a great deal of stress to be seat belted during transport. “He attempted to take off the belts and I explained that was a non-negotiable. I would like to give him two point five of versed intramuscular for his anxiety.” I rattled off the vital signs.

Dr. Phillips thought for a moment and said, “Well, I’d rather you give him Ativan. Versed can cause respiratory depression and I wouldn’t want to have any negative side effects.”

I rolled my eyes. “I understand, Doc, and I would rather give Ativan, too. But I don’t currently have Ativan. It’s not one of the drugs we carry.” I went on to tell him, briefly, about my current assignment working for our sister division and that they carry different drugs than we normally did. “I do have diazepam if you would prefer I administer that instead.”

He let out a sigh, “I mean, ativan would be the better option.”

“I agree, but since I don’t carry it, I’d like to give versed or diazepam.” I reiterated.

“Do you have an IV in place?”

“Not currently,” I replied, “His IV was removed at the hospital prior to transport. But I can administer intramuscularly.” I was getting more annoyed having to repeat my initial request for orders.

“Hmm, okay, go ahead and start and IV. Administer two milligrams diazepam via IV and put him on oxygen if his sats drop.” He stated. “And call back if you have any complications or need further orders.”

I nodded, even though he couldn’t see me. “I copy, Doc. One dose of two milligrams diazepam IV, oxygen as needed, and call back for further orders.” We cleared the phone call and I hung up.

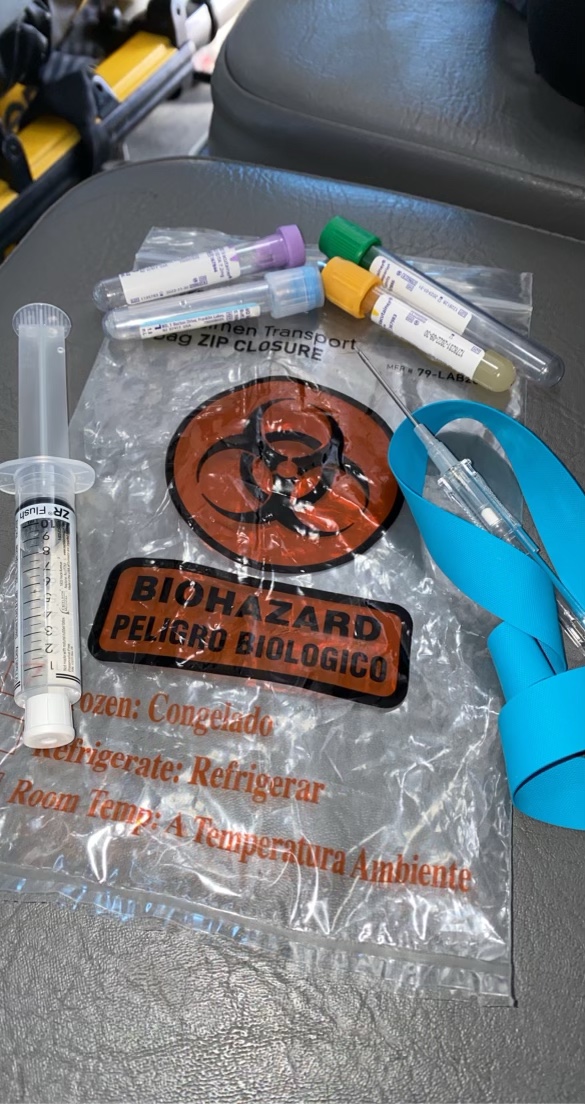

I moved back over to the bench and pulled out my IV supplies. “Okay, Sam, the doctor says I can give you a medication called diazepam. It’s also called Valium. You don’t have any allergies to medications, correct?” I already knew he didn’t because I read his file, but asking never hurt. Sam nodded his head and I proceeded. “To give it to you, I’ll need to start an IV.”

Tightening the tourniquet around his arm, I found a large vein at the inside of his elbow. There were also track marks up and down his arm. Scar tissue formed over his veins. I cleaned the site with an alcohol pad and uncapped the IV. With a “one, two, three, poke” I inserted the needle through his thick skin. I felt the needle give and I glanced down at the catheter. No flash. There was no blood return in the chamber, meaning I wasn’t in the vein. I fished around for the vein until I gave up.

“I’m sorry, Sam,” I said retracting the catheter and placing a piece of gauze over the spot, “I’m going to have to try again. I thought I had it.”

Sam said it was no big deal and pointed to a vein on his forearm. “Try here. This is the one I used to get all the time.”

Four or five sticks later, I still didn’t have the IV. Sam’s skin and the walls of his veins were thick with scar tissue. As an IV drug user, he’d really screwed me – and himself, because without the IV, I couldn’t give him the medication.

“What about this one?” Sam pointed to a long squiggly vein on the top of his hand. I took his fingers in my hand and used my thumb to pull the skin taut. The vein straightened out enough. I cleaned the area and uncapped a smaller gauge needle than I’d used before.

“Okay, one, two, three..” Poke. No flash. But I’d hit the vein! I knew I had! There was no way I had missed again! I apologized to Sam for the millionth time.

Sam shrugged. “It’s okay, you can keep trying if you want?”

The realization hit me. Sam hadn’t fiddled with the seat belts or cried or complained the entire time I was sticking him. He was enjoying this. His history of drug use had triggered his brain into anticipating a high that came with the pain of a needle piercing his skin. What I didn’t know was how long this would accommodate his anxiety.

By around the tenth or so attempt, I was getting annoyed at myself. I hadn’t been able to get a drop of blood from him. My IV skills weren’t anything super exceptional, but I was usually able to get a stick when I absolutely needed to.

I looked up at Sam who was still gazing at the needle in his arm that I hadn’t yet released. “I’m running out of places to try. I’m sorry, Sam.” I noticed the change in his face. The anxiety restored. The fidgeting. “If you can hang tight for a few minutes, I’ll call the doctor back and ask if I can give it to you another way.”

Sam slumped back in the gurney and I returned to my airway seat to call the hospital.

After the nurse connected me with Dr. Phillips again, I explained the situation. “I’ve stuck this guy, like, twelve times, Doc. Can I give the versed or diazepam IM?” Like I originally asked, I thought.

Dr. Phillips was quicker with his decision this time. “Yes, go ahead and give two milligrams diazepam IM, no repeat dose. And call back if you need further orders.”

I explained to Sam what I was going to do. No more IV sticks, I was going to give him a shot in the arm. Sam agreed to the treatment and I made myself busy cleaning his arm. I drew up the drug in a syringe and pushed the plunger into the muscle. I covered the tiny drop of blood with a Band-Aid and sat back in my seat.

“We’re almost there, Sam. You’re doing great.” I reassured.

Sam continued to tell me for the next thirty minutes that the medication wasn’t working. He continued to finger the seat belts. I reassured him he was safe and everything would be fine. I was not about to call Dr. Phillips for a third time.

As we pulled into the ambulance bay at the behavioral hospital, I allowed Sam to unbuckle his seat belts. At this point, I didn’t care about protocol. We let Sam walk inside instead of remaining on the gurney. I was chastised by the receiving nurse, and even after explaining my reasoning for unrestraining the patient before care was taken over, she didn’t want to hear me.

I obtained my signatures and Summer and I walked out of the building.

“So how many times did you stab that guy?” Summer asked as we cleaned the gurney and disposed of all my garbage from the back.

“I lost count.” I admitted. “But the weird thing was, I think he liked it.”

Summer and I both shivered at the thought. It wasn’t my idea of a good time. But sometimes you just gotta stab someone to get them to leave you alone.